gRPC in practice - directory structure, linting and more

Let’s do a short recap

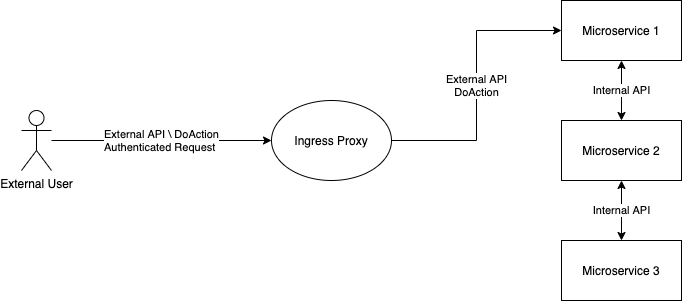

We have many microservices. Each microservice has external APIs that can called by authenticated users. It also has internal APIs can be called internally by other microservices. The communication is done using gRPC.

We are still a small team and our goal is to keep moving as fast as possible. This means that the infrastructure must serve us and adding features should be simple.

We use GoLang for backend and JavaScript (TypeScript + VueJS to be exact) for frontend. Everything below was done to make the use of gRPC easy in the context of that environment. Nevertheless, it should be very similar in other languages.

How are proto files transformed to code?

Below is a short excerpt that explains what a proto compiler is, referenced in as protoc in the article.

When you run the protocol buffer compiler on a .proto, the compiler generates the code in your chosen language you’ll need to work with the message types you’ve described in the file, including getting and setting field values, serializing your messages to an output stream, and parsing your messages from an input stream. For Go, the compiler generates a .pb.go file with a type for each message type in your file. — Source Google Documentation

In addition to generating the messages, when coupled with the gRPC plugin a gRPC service interface and gRPC client will be generated.

A single container with all the tools

All of our gRPC/proto tools are baked into a single docker container. This allows us to ensure that all the developers and the CI are running with the same versions of tools and plugins. Moreover, developers don’t have to install 10s of different tools and execute complex configuration scripts on their development machines. Everything they need to work is in the container.

The container is coupled with a handy Makefile. The Makefile which is optimized for our internal usage and provides commands such as make proto or make jsproto to compile proto files into Go or JavaScript. Each compilation is performed only after a linter is executed to validate coding conventions and backward compatibility.

gRPC plugins that we use

- protoc-gen-grpc-gateway — plugin for creating a gRPC REST API gateway. It allows to expose gRPC endpoints as REST API endpoints and performs translation from JSON to proto. Basically you define a gRPC service with some custom annotations and it makes those gRPC methods accessible via REST using JSON requests.

- protoc-gen-swagger — a companion plugin for grpc-gateway. It is able to generate swagger.json based on the custom annotations required for gRPC gateway. You can then import that file into your REST client of choice (such as Postman) and perform REST API calls to methods you exposed.

- protoc-gen-grpc-web — a plugin that allows our front end communicate with the backend using gRPC calls. A separate blog post on this coming up in the future.

- protoc-gen-go-validators — a plugin that allows to define validation rules for proto message fields. It generates a Validate() error method for proto messages you can call in GoLang to validate the message matches your predefined expectations.

Coding conventions

When working in a team it’s important to define common conventions guidelines that all the developers will follow. Ideally you’d want a linting tool to enforce those conventions.

We are using the excellent prototool as our linter. It’s configured to suit our personal preferences. A mix of rules from Google’s proto style guide and Uber’s V2 style guide. We are still optimizing the configuration so it won’t be too annoying. The rules below is what we currently use.

{

"excludes": [

"protodep",

"js"

],

"protoc": {

"version": "3.11.4",

"includes": [

"/project",

"/protodep"

],

"allow_unused_imports": true

},

"lint": {

"group": "google",

"rules": {

"add": [

"COMMENTS_NO_C_STYLE",

"COMMENTS_NO_INLINE",

"ENUMS_HAVE_COMMENTS",

"ENUMS_NO_ALLOW_ALIAS",

"ENUM_FIELD_NAMES_UPPER_SNAKE_CASE",

"ENUM_FIELD_PREFIXES_EXCEPT_MESSAGE",

"ENUM_NAMES_CAMEL_CASE",

"ENUM_NAMES_CAPITALIZED",

"ENUM_ZERO_VALUES_INVALID_EXCEPT_MESSAGE",

"FIELDS_NOT_RESERVED",

"FILE_HEADER",

"FILE_NAMES_LOWER_SNAKE_CASE",

"FILE_OPTIONS_GO_PACKAGE_NOT_LONG_FORM",

"FILE_OPTIONS_GO_PACKAGE_SAME_IN_DIR",

"FILE_OPTIONS_REQUIRE_GO_PACKAGE",

"IMPORTS_NOT_PUBLIC",

"IMPORTS_NOT_WEAK",

"MESSAGES_HAVE_COMMENTS_EXCEPT_REQUEST_RESPONSE_TYPES",

"MESSAGE_FIELD_NAMES_FILENAME",

"MESSAGE_FIELD_NAMES_FILEPATH",

"MESSAGE_FIELD_NAMES_LOWER_SNAKE_CASE",

"MESSAGE_FIELD_NAMES_NO_DESCRIPTOR",

"MESSAGE_NAMES_CAMEL_CASE",

"MESSAGE_NAMES_CAPITALIZED",

"NAMES_NO_UUID",

"ONEOF_NAMES_LOWER_SNAKE_CASE",

"PACKAGES_SAME_IN_DIR",

"PACKAGE_IS_DECLARED",

"PACKAGE_MAJOR_BETA_VERSIONED",

"PACKAGE_NO_KEYWORDS",

"REQUEST_RESPONSE_NAMES_MATCH_RPC",

"REQUEST_RESPONSE_TYPES_AFTER_SERVICE",

"REQUEST_RESPONSE_TYPES_ONLY_IN_FILE",

"REQUEST_RESPONSE_TYPES_UNIQUE",

"RPCS_HAVE_COMMENTS",

"RPC_NAMES_CAMEL_CASE",

"RPC_NAMES_CAPITALIZED",

"SERVICES_HAVE_COMMENTS",

"SERVICE_NAMES_CAMEL_CASE",

"SERVICE_NAMES_CAPITALIZED",

"SERVICE_NAMES_MATCH_FILE_NAME",

"SYNTAX_PROTO3",

"WKT_DIRECTLY_IMPORTED",

"WKT_DURATION_SUFFIX",

"WKT_TIMESTAMP_SUFFIX"

]

}

}

}

Our most “sacred” conventions

- Package name must make sense and must be versioned —

package com.stackpulse.internal_api.service1.v1 - Request message suffix is

Request—CreateUserRequest - Response message suffix is

Response—CreateUserResponse option go_packagemust be a fully qualified path to a go package —option go_package = "github.com/stackpulse/service1/api/internal-api/v1- Internal API can reference External API but not vice versa. More on this in the next blog post about gRPC for the front end.

Structuring proto files

The first big decision we had to make was how to organize the proto files. While researching this, it seemed that a single repository that contains all the proto with all their dependencies was the most popular method.

A single proto repository

This approach is what I call Interface First. You have to define all your interfaces first, update the proto files in a central proto repository. Once those changes were accepted you start writing your service’s code. Each additional change to the interfaces or proto messages requires going through this loop again.

The directory structure of such repository may look like this:

├───github.com

│ ├───stackpulse

│ │ ├───service1

│ │ │ ├───v1

│ │ │ │ └───service1.proto

│ │ ├───service2

│ │ └───service3

│ └───thirdtparty

│ └───project

└───google

In short, the directory structure is based on GoLang conventions. Each module is placed in a directory tree that contains the origin of the module (for example the git repository that contains that module github.com/stackpulse) and the module name (service1). This structure also makes it particularly convenient when Go is your main programming language because many of the proto dependencies that you will use are also Go modules.

The google libraries are a slight exception to the rule as the common what to reference them is not using the full module path, but just with google as the prefix (import "google/api/annotation.proto").

Even though this was, what seemed to be, the common method, we decided to choose a different path, which resulted in some initial headache.

In retrospect, I think that if a single repo works for you, by all means go for it. A single proto repository will solve a lot of pain involved working with the proto compiler and the different plugins. It’s very intuitive.

Don’t get me wrong, it still wont be a walk in the park and you will probably encounter quite some challenges during the initial adaptation period. There are also some challenges there with packaging the compilation results of proto files.

I won’t be covering those, since we didn’t go that way.

Our method: protos in the service repository

The method we chose was putting the proto files inside the service’s repository.

Below you can see an example layout of the different services in our github account github.com/stackpulse. Each service is a different git repository.

├───service1

│ │ go.mod

│ │

│ └───api

│ │ go.mod

│ │

│ ├───external-api

│ │ └───v1

│ └───internal-api

│ └───v1

├───service2

│ │ go.mod

│ │

│ └───api

│ │ go.mod

│ │

│ ├───external-api

│ │ └───v1

│ └───internal-api

│ └───v1

└───service3

│ go.mod

│

└───api

│ go.mod

│

├───external-api

│ └───v1

└───internal-api

└───v1

Under each service’s repository:

- There is an api directory, which is a go module in itself. Other services may reference it using Go Modules.

- Proto files reside either in api/external-api or api/internal-api depending on their responsibilities.

- Proto files are compiled using the protoc compiler. The compilation results for Go are stored next to the proto files in either

api/external-apiorapi/internal-apidirectories. They are committed to source control just like regular code.

We like this approach because:

- Modifying a proto file is just like modifying the code. It’s just a file inside the repository and it can be done rapidly during microservice development.

- Proto files and their compilation results are versioned together with the code that implements the servies.

- If

service1wants to talk toservice2using a gRPC client, it will use go modules to fetchservice2‘s compiled proto messages and clients. It can reference the auto-generated client code and the message structs to easily communicate withservice2using native Go tools.

How do we manage 3rd party dependencies?

One may ask, how do you manage dependencies for 3rd party proto modules? What happens when service1 wants to include service2 proto message as a part of its own proto message?

message Service1Message {

service2.Service2Message test=1;

}

We use the excellent protodep tool. It allows us to define a TOML configuration file with all the dependencies a service needs. This can be 3rd party modules or another internal service it needs.

Protodep is able to parse the TOML file and download all the dependencies to a sub directory. Our proto-builder container takes the dependencies directory and restructures it alongside the microservice’s proto files into a directory layout that resembles a single proto repository I described earlier.

The protoc tool is then able to work with the directory tree easily and compile proto files to the target language.

proto_outdir = "./protodep"

[[dependencies]]

target = "github.com/mwitkow/go-proto-validators"

branch = "master"

path = "github.com/mwitkow/go-proto-validators"

ignores = ["./test", "./examples"]

[[dependencies]]

target = "github.com/grpc-ecosystem/grpc-gateway/third_party/googleapis/google/api"

revision = "v1.14.1"

path = "google/api"

[[dependencies]]

target = "github.com/grpc-ecosystem/grpc-gateway/protoc-gen-swagger/options"

revision = "v1.14.1"

path = "protoc-gen-swagger/options"

[[dependencies]]

target = "github.com/protocolbuffers/protobuf/src/google/protobuf"

revision = "v3.11.4"

path = "google/protobuf"

ignores = ["./compiler", "unittest", "test_messages_", "any_test", "map_lite_unittest", "map_proto2_unittest", "util", "map_unittest"]

[[dependencies]]

target = "github.com/stackpulse/service2/api/internal-api/v1/"

path = "github.com/stackpulse/service2/api/internal-api/v1/"

branch = "master"

We only commit the protodep.toml and protodep.lock files to source control. The protodep directory which contains the assets the tool downloads is not committed into source control (just as you wouldn’t normally commit node_modules).

Organizing APIs into Internal and External

When building gRPC services we separate them into 2 categories.

- Internal APIs— The stuff we do behind the scenes that we don’t want exposed. This API can only be called internally and there is no way to reach it from the outside.

- External APIs — Think about this as your public API. Authenticated users have access to it, either using one of our SDKs or using our management portal. This API is entirely public and should expose only specific tasks. Basically everything defined here, the gRPC services and the proto messages are open to all. This makes it important to disallow including Internal API anywhere in the externally exposed proto files and gRPC services.

How does authentication to External API work?

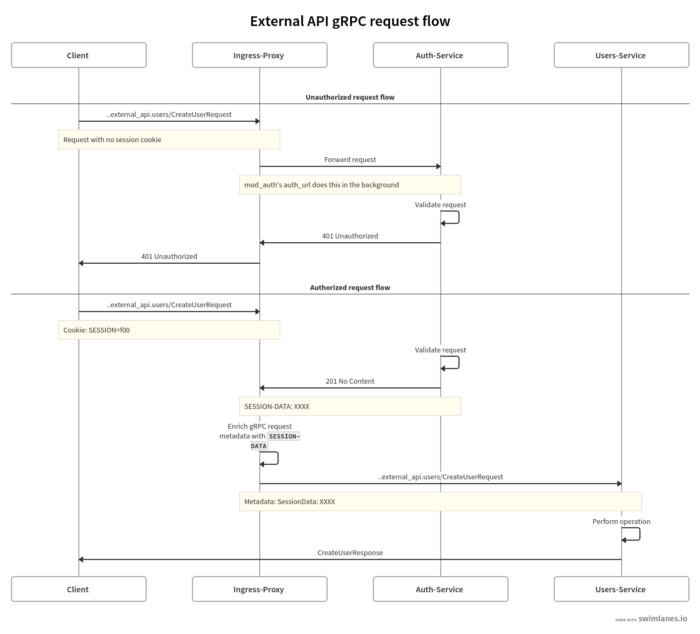

External API is exposed using our NGINX ingress controller to the outside world. Since each of our gRPC services lives under a well defined package name we are able to route external traffic to external services

location /com.stackpulse.external_api.service1 {

grpc_pass grpc://service1;

}

After successful authentication each user gets a session cookie that ensures they are logged on into our system. We use the powerful ngx_auth_request_module to validate user’s session cookie. If the module recognizes the session it enriches the grpc metadata with the user’s session data.

Using a middleware defined for the given gRPC services implementation in GoLang we are able to check if the session is indeed included in the metadata, and if not disallow the request.

In the next chapter

In the next chapter we will go into some additional implementation details of authentication is implementation and discuss how to use gRPC on the client side in your JavaScript frontend.